Visual Artist (1984) based in Santiago de Chile.

Mañana es mejor / Tomorrow is better

We enter Benjamín Ossa's new exhibition, promisingly titled Mañana es mejor (Tomorrow is better). We find drawings in various media and formats, as well as photography; finally, a pair of sculptures that move without haste but without pause. A wide range of materialities is associated here, and the relationship between the artworks becomes part of the art itself. Materiality by materiality, we will explore the poetics of each artwork present, the depth that the show conspires as a whole: how Ossa, instead of repeating himself, seeks a matrix in uncertainty and, by doing so, gives us clues about his intimacy.

"I don't know if things come, go, rise or fall” (“No sé si las cosas vienen, van, suben o bajan”). This is how the artist titled a previous series of his drawings. "I don't know": this assumption of uncertainty is typical of mystics. With that denial they warn us, in a Socratic tone, that the only thing they know is that they know nothing. It is like a warning sign hung on the portal that separates the conceptual from the sensible. "I don't know" repeats three times César Vallejo - the most defiant poet of the Spanish language - in the entrance poem to his first book. "I don't know": by realising that ideas are also limitations, we come to experience language in a way that no idea manages to represent. In a word: poetry, something made of language, but meant beyond communication. There, Vallejo declares his mystical vocation. Ossa's aforementioned title continues, "I don't know if things...". We are thus rooted in concrete experience. His uncertainty is that of the artist who thinks through the handling of his materials. About those things, the artist does not know if they "come, go, rise or fall": he leaves us in the realm of relativity. And it is coherent that he progressively deepens in the most relative and therefore most challenging material of visual art: color. These are drawings that increasingly reflect about painting. With his mixtures of layers of flat colored papers, Ossa repossess the visual grammar from its foundations, but with playfulness and improvisation.

A good example of Ossa’s analytical games is the series of drawings entitled "Red net" included in Mañana es mejor. They are cut drawings, back-lit, where shadows are cast by semi-circular tabs cut and folded on the support. This is a way of drawing that Ossa has been exploring in variations since 2011. Evoking his large-scale sculpture in by the seaside (Habana Biennale, 2020) these are malecones that he cuts to adorn with shadows, partly hiding - that is, erotically - the source of light underneath the drawing. Imagining these artworks in relation to architecture, I would say that Ossa opens Matta-Clark's wall holes in a scale and material similar to the models photographed by Thomas Demand. What forms do these drawings suggest? Circles of varying size that bring to mind constellations of macro- and microcosms. Planets with moons around them, also atoms, molecules. These circles float, impact one another; their radii sometimes suggest sonar waves or visualisations of networked echoes. In an interview, Ossa said that he likes how these forms "float without a point of reference", that he wants to "let the forms wander": not knowing if they "come, go, rise or fall". This speaks about a will to make art from hesitation, from the heart of doubt, and that this aspect of the making remains palpable in the result.

Circles. Centers. The artist has said that "to stay concentrated" is one of the daily challenges of his artistic process. Who would not empathise, in this age of stimuli saturation? Ossa has also commented on the pleasure he takes in realising how his "different projects start to converge with each other”. We can see and think of the superimpositions, echoes and radiations of the concentric and eccentric forms of these drawings as a representation of the convergence that the artist has found through a sustained search.

The circle is the primordial. Not only in the ancestral past when a hypothetical hominid saw the full moon shining round in the night sky and copied it in the sand with a stick, then with charcoal on the wall of a cave, from where millennia later rolled the coin and the disk that very same shape— the circle also remains an incessant origin in the present. According to D. Winnicott, crucial childhood psychoanalyst, the circle represents the first symbol of the inner world for infants. The closed origin as a starting point. The womb that engulfed us, from which we are born exiled: the mother, the first other. Each new human life tends to recognise the circle before any other geometric form. Moreover, the perfection of the circle implies the closing of every course. From alpha to omega, it is the result of a movement, the fulfilment of a cycle. No wonder that sundials and most clocks are round! And that both time and movement are crucial concepts to understand the work of Benjamin Ossa.

Further "Dibujos para perderse" (“Drawings to get lost”) complement the series mentioned above. They are large format drawings made with tiny gestures. Drawn with silver ink on a black surface, they are essentially graphic. Their title evokes their process: Ossa has begun by drawing a grid by hand; then, using a metal circle that is a remnant of a previous sculpture (and a preamble to the sculptures we will relate at the end of this text), he has traced curves that playfully converge. Faithful to his will for analytical gaming, the increasingly smaller zones that these converging curves circumscribe result in a sort of chessboard whose checkboxes, progressively compressed, are filled with silver or left empty (in black), with increasing random openness and a certain labyrinthine tendency. The more the gridded spaces are reduced, the more the gesture of the hand becomes evident, which results - especially when viewing these works from a distance - in a certain vibration. That is why these drawings, departing from the control of the grid, are "to get lost". About them, the architect G. Hevia has written "What differentiates these drawings from a precise edition made with digital instruments? The existence of almost imperceptible errors, [milli]metric inconsistencies [...], the impossibility of redoing or going back, [setting] the analog over the digital. Aspects that we could consider errors or imperfections are precisely those moments in which control is lost."

Mañana es mejor also includes a series of shattered mirrors. They are mirrors that Ossa broke on purpose, against the establishment of a reflection that threatens to stiffen identity. The resulting shreds make networks, grids... a kind of random drawing, whose form tends to branch out like veins. Both the shape of the shredding and the material of the mirrors are associated with the photographs described below.

Photography, an artistic language that is being installed as a parallel melody in Ossa's work, especially through his books, also abounds in the exhibition. In 2015, the artist took hour after hour a series of photographs in the Atacama Desert that submit a sort of clock made of celestial hues, propounding a colorful record of the earth's rotation. Continuing his emphasis on making the passage of time sensual, Mañana es mejor includes a series of photos titled Isluga, also taken in 2015 near the Chilean town of the same name. They show vestiges of a guessed party: details of broken bottle fragments and half-buried bottle caps. In these photographs, taken at noon between 11:50 and 12:00, the shards of glass reflect the sunlight in the absence of cast shadow typical of midday. Printed on metallic paper, their contrast is reminiscent of both the “Dibujos para perderse" and the shattered mirrors mentioned above.

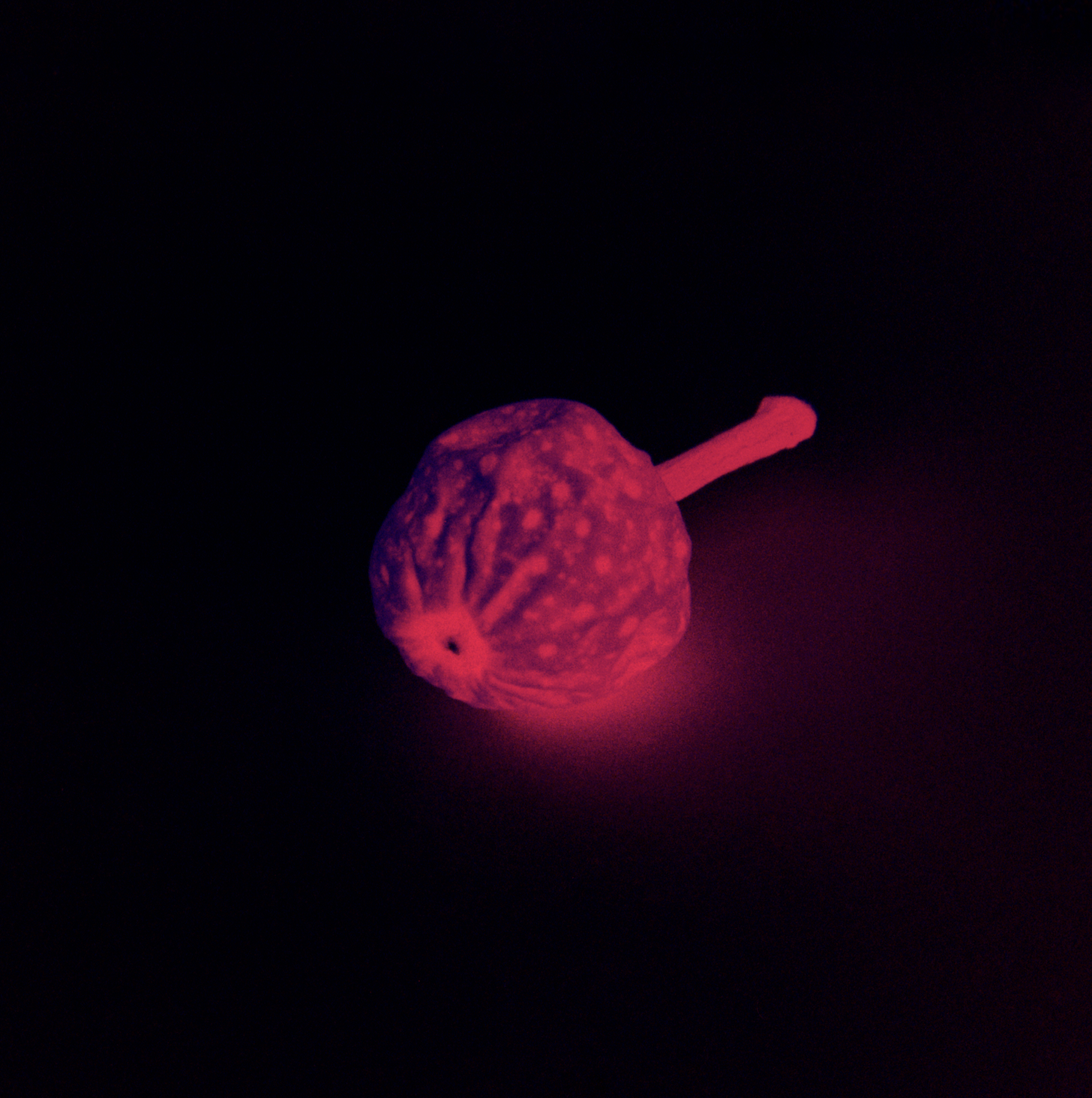

Two other photographs in the show detail the veins of the artist's eye, red and branching against the white of his sclera: hence their title, “Los hombres te miran te quieren tomar” (“Men look at you and want to take you”). Also reminiscent of the shape of the eye are four photographs of fuchsia seeds. About the seeds, he has observed that "they become active when the environment is favorable". Any material - depending on the temporal scale with which we conceive of it - accounts for moments of a process. Palpably organic matter, as is the case with seeds: they are objects to be activated, just like Ossa's works. The photographed seeds are part of the artist's personal object collection. About them, Ossa admits that "most of the ones I keep, I don't know what tree they come from or what plant they go to. They are usually gifts from my children.” For several years now, Benjamín Ossa has been seeding his children with the curiosity that constitutes him as an artist. "Bring me whatever you find interesting," he began by inviting them, after which they began to bring him objects shown with the question, "Dad, will this do?". Thus, the seed photos are aptly titled “¿y para quién?” (“and for whom?”). The association of the photographs of eyes and seeds with the shattered mirrors raises a map of symbolic relationships.

Entitled "En un momento vas a ver que ya es la hora de volver” (“In a moment you will see that it is time to come back”), the sculptures of Mañana es mejor embody the relationships between the drawings and photographs included in the exhibition. They are two volumes or spatial drawings made of metallic circles. These circles make us think of the orbits represented in a planetarium that would omit the planets. But these are not ellipses, but circles of equal diameter. It is essential that these are sculptures in motion. Their moving shadows cast shifting graphics over the exhibition room. The circles that make up these sculptures have the same diameter as the circular piece that Ossa used for tracing the curves of "Dibujos para perderse". These sculptures remind me of a comment by Hevia on the artist's books, for, like those books, they provide "a window into the engine room that sets in motion the whole ouvre”.

In this way, the shadows cast by the sculptures propose a music of the spheres that relates the various artworks of the exhibition. But this is a personal music. Which invites us to clarify that the title of the exhibition is taken from a song written by Argentinian musician Luis Alberto Spinetta (Cantata de Puentes Amarillos, from the album Artaud recorded with his band Pescado Rabioso, 1973) and that also "Los hombres te miran te quieren tomar" (the title of the photographs of the artist's eye veins), "y para quién?" (the title of the photographs of seeds) and "En un momento vas a ver que ya es la hora de volver" (the title of the sculptures in motion) are also verses from the same song. This Spinetta song has accompanied the artist's process, and the use of its verses as titles of works is a coordinating gesture that links us to his laboratory of affects.

In Mañana es mejor, Benjamín Ossa opens himself to uncertainty as his material of preference. He pursues it materiality after materiality, turning grids into games. Letting go, exposing himself vulnerable, allowing the "I don't know" of mystics to emerge and materialise. Letting go of certainties, he assumes the vertigo of what is not destined. In Mañana es mejor, the recurring forms of Ossa's compositions reverberate in his intimacy and return as affirmative echoes, redefining his work with greater affect. As a final comment that may underline the personal dimension of this exhibition, allow me the following confidence: the writer of this text is a poet, once a fellow artist mate in some of Ossa’s first group exhibitions. Since then, it has been a great joy to mutually follow the development and resonance of our poetics. For that reason, writing this reflection on an exhibition that proposes an entrance to the mystery that is always the everyday, reaffirms a friendship that, to quote another song, it's getting better all the time.

Tomás Cohen, December 2022.